Introduction:

This is an overview of the concept for the second game I develop as part of the Games and AI module which includes a discussion of behavior trees and resource management AI which I plan to use as blueprints for the development of two distinct player opponent system in Unity 2019.3.

Game Concept:

The concept of the game is a top-down shooter where each stage is represented through a building which the player navigates through to locate a keycard and use it to open the exit, located at a fixed position, and escape which completes the level. The keycard spawns randomly between multiple predefined locations each playthrough. The player can encounter two different archetypes of opponents, a scout and a grunt (mobility vs resilience), which are designed to coordinate their moves in teams of various sizes in an attempt to eliminate the player. The enemies are spawned and instructed by a director AI which uses limited resources in a given time frame to influence the game using data collected from each enemy encounter.

AI Concept:

The director AI has limited pool of resources per level for the duration of a specific time interval which it uses to spawn new agents and issue instructions to existing ones in real-time. It’s ultimate goal is to use its resources as efficiently as possible in an effort to construct optimal strategies of eliminating the player character based on its collected data.

Each agent has a different behavior tree designed around one of two identified enemy archetypes. It’s goal may change dynamically based on the outcome of its encounters with the player. When wounded a grunt would attempt to find and take cover if any is available nearby, while a scout would attempt to retreat to a set distance from where it encountered the player and inform multiple nearby agents of the player’s last known location. This facilitates a framework for setting up particular strategies to be evaluated and set in motion by the director AI which if balanced appropriately towards a certain difficulty can present unique challenges for players of different skill levels.

Resource Management AI:

The resource management AI would collect data from each agent encounter with the player which will allow it to store the player’s last known position, the success rate of combat with each agent based on the number of shots hit and received during the encounter and the distance between an agent and the player during the encounter.

The resource management AI would be restricted to spawning enemies only outside of the player view with a specific cooldown on each enemy archetype spawned to balance the game in favor of the player.

The resource management AI would be able to issue instructions to agents in specific circumstances where it cannot spawn agents or has identified a higher success chance following a different strategy. These instructions can range from updating the agent’s last known player location in an attempt to encourage a combat encounter or flank the player, instructing it to coordinate an attack with other agents or retreating prematurely to utilize a combat encounter in a location with a higher success chance.

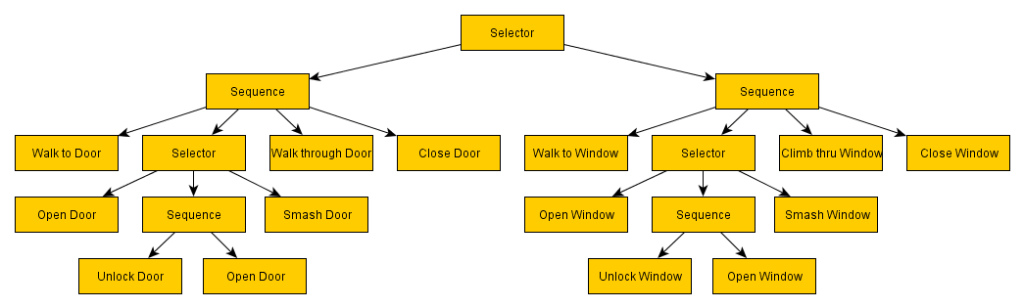

Behavior Tree:

The behavior trees would be implemented with two distinct archetypes in mind, a scout and a grunt, designed around complementing each other’s strengths and weaknesses and improving their odds of success when used appropriately by the resource management AI.

The behavior tree will follow a sequence-based design approach where multiple actions are undertaken when a criteria is met for a specific sequence.

The Scout:

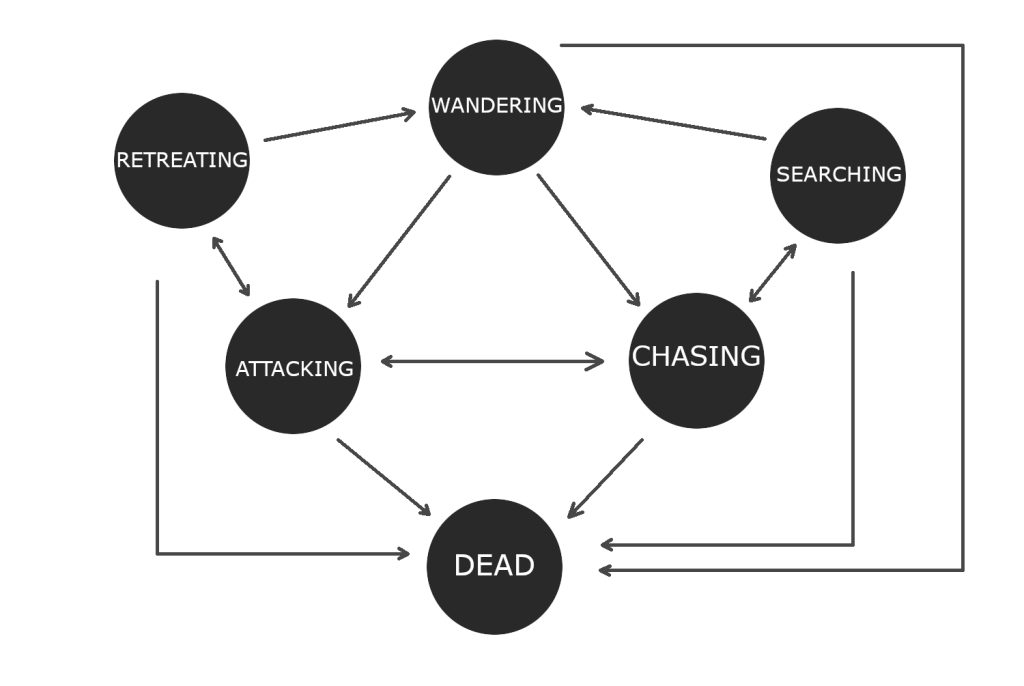

The scout archetype would be designed to gather continuous data for the resource management AI and assist other nearby agents in combat by being implemented with movement speed matching the player’s but lacking in health points and the damage dealing. An agent with this behavior tree starts out by actively patrolling an area by travelling between four waypoints assigned by the resource management AI and experience transitions in behavior when encountering the player at different distances or being instructed by the resource management AI based on specific circumstances.

The grunt:

The grunt archetype would be designed primarily for combat encounters as it’s characteristics improve the odds of eliminating the player when used effectively with a scout. The grunt features a health pool matching the player’s and is able to deal more damage per second but is lacking in movement speed and can easily be kited by the player which leaves it vulnerable on its own in combat. An agent with this behavior tree starts out stationary, guarding a specific area in a radius of its location and experiences transitions in behavior when the player is within this radius, it has direct line of sight of the player or when it is instructed by the resource management AI or a nearby scout agent.

Credits:

- Featured Image: https://www.gamewatcher.com/news/2017-27-04-warhammer-40k-dawn-of-war-iii-patch-notes-patch-0#

References:

- “In the Director’s Chair”: https://aiandgames.com/in-the-directors-chair-left-4-dead/

- “An adaptive AI for real-time strategy”: http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:3328/FULLTEXT02

- Behavior Tree: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Behavior_tree_(artificial_intelligence,_robotics_and_control)

- “Are behavior trees a thing of the past?”: https://www.gamasutra.com/blogs/JakobRasmussen/20160427/271188/Are_Behavior_Trees_a_Thing_of_the_Past.php

- “Behavior Trees: Three ways of cultivating Game AI”: http://twvideo01.ubm-us.net/o1/vault/gdc10/slides/ChampandardDaweHernandezCerpa_BehaviorTrees.pdf + GDC Talk: https://www.gdcvault.com/play/1012416/Behavior-Trees-Three-Ways-of

- “Building your own Basic Behavior tree in Unity”: https://hub.packtpub.com/building-your-own-basic-behavior-tree-tutorial/

- “Behavior Trees for AI, how do they work?”: https://www.gamasutra.com/blogs/ChrisSimpson/20140717/221339/Behavior_trees_for_AI_How_they_work.php